Majority Voting:

Let us assume that there are three individuals in the society X, Y and Z and there are three alternative outcomes a, b, and c. There is pair-wise comparison of the outcomes and the transitivity rule is valid for the individual preference as well as the group preference; i.e. if 'a' is preferred to 'b' and 'b' is preferred to 'c' than 'a' is preferred to 'c'

For individuals X and Y, b > c for individuals Y and Z, c > a. It means the majority (two out of the three) individuals prefer 'b' to 'c' and 'c' to 'a' therefore 'b' is preferred to 'a' due to the transitivity rule. Pair-wise comparison of 'b' and 'a' also conforms to b>a by the majority rule. Therefore according to the majority rule the group choice is b>c>a and it coincides with the preference pattern of individual Y. In this case individual Y is known as the 'Median Voter'.

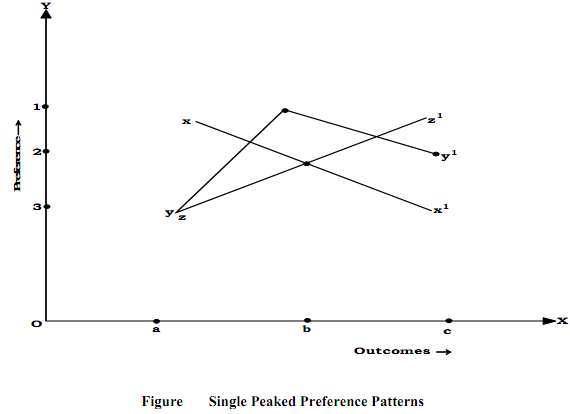

The preference patterns of X, Y and Z are given in Figure 6.1. Here preferences are single peaked in the sense that they either increase or decrease steadily (as in the case of X and Z) or have a single peak or maximum (the case of Y). Therefore it is known as the Single Peaked Preference Patterns and it identifies the Median Voter Y.

Let

X: a > b > c

Y: b > c > a

Z: c > a > b

According to the majority rule b >c and c > a => b > a (transitivity rule). However a > b according to the majority rule. It contradicts. This is known as 'Cyclic Voting' and leads to a paradox in decision-making. In this case there is no median voter and it gives a non-single peaked preference pattern. In Figure 6.2 the preference pattern of Z is not single peaked as it forms a valley rather than a peak. The characteristic of a single peaked preference essentially means that the middle range alternative stands between or above the two extremes. This is true in Figure 6.1 but in Figure 6.2 Z has no consistent pattern; he prefers either extreme to the middle range. Hence there is no single peak, Z has double peaked preference pattern.

In the case of non-single peaked preference pattern of voting there is the possibility that minority can thwart the preference of the majority if there is asymmetric information. This can be proved as follows:

To take admission for a professional course suppose there are three groups of students such as:

X (Poor and meritorious),

Y (Rich and meritorious),

and Z (Rich and average merit)

Suppose good private institutions are admitting students on the basis of amount of donation giving less importance to the merit of a student. Banks are providing Education Loan. These three groups are revealing their preference on following three types of consideration for admission. The student union will pressurize the government to intervene in the admission of private professional institutions considering the views following majority rule.

a → No donation only merit,

b → Donation and merit,

and c → Only donation with average merit.

X: a > b > c

Y: b > c > a

and Z: c > b > a

Applying majority rule the group preference will be b > c > a and Y will be the Median Voter. This results in a single peaked preference pattern as given in Figure 6.1. However suppose the minority group Z in this case apply strategy voting misrepresenting its true preference and the other two groups cannot discover it before hand. It results in

X: a > b > c

Y: b > c > a

and Z : c > a > b

It results in a non-single peaked preference pattern as described in the Figure 6.2 leading to the Cyclic Voting i.e. a paradox. No group preference can be derived in this case, so no intervention by the government. The admission process is continuing as it is and it coincides with the first preference of group Z (minority) thwarting the preference of the majority.

If there is no asymmetric information and X and Y apprehend the strategy of Z, they might take the counter- strategy in the following manner.

X : a > b > c

Y : b > a > c

and Z: c > a > b

In terms of majority rule the group preference will be a > b > c and X will be the Median voter.