Empirical Tests:

The improbability of all the above assumptions casts doubt on the Tiebout proposition. So how can we test whether fiscal conditions play any role in the decision to reside in a local community? There are at least two approaches. One looks at the relationship between fiscal conditions and house prices, the other looks at fiscal preferences and residence.

1) W. Oates focused on education expenditures per pupil and used this as a measure of the quality of public services in 53 northern New Jersey municipalities. If property is fixed, then, as people move into an area that has a superior set of public services, they will drive up property prices in that area. Oates found that property values were negatively correlated to the tax rate. He also found that school expenditures per pupil and property values were positively related, i.e. that additional fiscal spending attracted an inflow to the locality. These results support the hypothesis that individuals are willing to pay more in order to live in communities that provide high-quality services. However, this test has attracted.

2) Gramlich and Rubinfeld examined responses to survey questions. If the Tiebout mechanism is relevant, then there should be some effect of the costs of moving on the pattern of preferences; that is, when there are many localities it is easy for individuals to move to the one they most prefer, and hence there should be a greater homogeneity of preferences within those localities. They confirmed there was substantially greater homogeneity of demand within suburbs located near many other communities. By contrast, where there were few other communities exit was less easy and there was more heterogeneity.

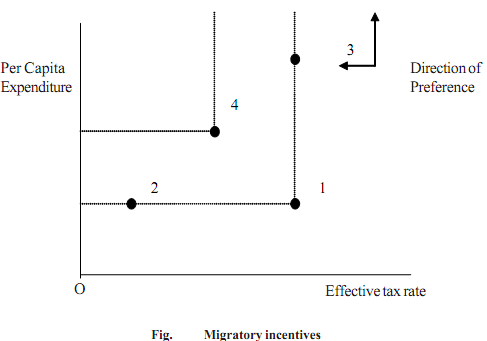

3) Studies by Aaronson and Schwartz and Aaronson indicate that, in both the USA and UK, the mix of public goods and tax rates has an effect on how population is distributed among governmental units. Aronson and Aronson and Schwartz develop a framework that indicates relatively attractive destinations. In Figure 3.3 the axes measure a 'bad' effective tax rate (x axis) and 'good' per capita local government expenditures (y axis). For anyone in jurisdiction 1, any location to the north (3), west (2) or north-west (4) generally must be superior (less of a bad, more of a good or both). Hence jurisdictions should gain population relative to 1 if they are at, say, 2, 3 or 4. The process can be repeated for jurisdiction 4. The test the authors apply is that destination jurisdictions 2, 3 and 4 should gain residents relative to the origin town 1. Evidence from local government areas in both the UK and the USA offered empirical support.