Replication cycle

The complexity and range of virus types are echoed in the various strategies they adopt in their replication cycles. Viruses, as obligate intracellular parasites, must attach to and penetrate suitable host cells in order to undergo a reproductive cycle. This cycle is highly dependent on the metabolic machinery of the cell; all viruses lack the machinery to generate ATP or to synthesize proteins, and many other varied enzymes, proteins, and processes may be required. As a result, in most cases the virus takes over the cellular processes and orchestrates them towards its own replication. This usually results in the inhibition of host cell protein and nucleic acid synthesis, although some viruses allow cellular processes to continue for a period, and may even stimulate them (such as the human papillomavirus, which relies on continued cellular DNA synthesis in order to replicate its own genome). The cycle has a number of stages – attachment and nucleic acid synthesis penetration, and transcription, protein synthesis, assembly, maturation and release. The outcome is the production of hundreds of progeny virions that leave the infected cell (by lysis or budding), ultimately killing the cell and spreading to infect more host cells and tissues.

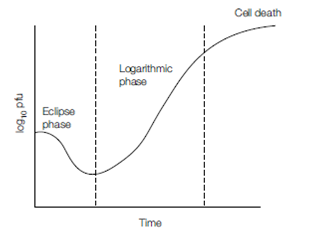

The stages of the replication cycle can be visualized indirectly using infected culture cells; following the addition of virus to the culture at a high m.o.i. (i.e. all cells are infected simultaneously), the amount of extracellular virus can be monitored by an infectivity assay, testing samples at regular intervals over time. Virus replication occurs within all cells synchronously and the changing level of extracellular virus reflects the replication cycle. This is often called the one-step growth curve and a typical representation is shown in, where extracellular virus levels are shown on the y-axis, against time on the x-axis. Following virus attachment to, and penetration into, cells the level of extracellular virus falls, seen during the eclipse phase. During the early stages of virus replication, there is a period when no new virions are released (extracellular virus remains low), but following the start of virus assembly and release by virus, cells are lysed and increasing numbers of cell-free virions are detected (the logarithmic or expansion phase). As the cells reach the end of their capacity and the effects of virus replication take their toll, the numbers of new virions begin to plateau as the cells inevitably die (death phase). The shape of the one-step growth curve naturally varies greatly between viruses. For many bacteriophages it takes less than 60 minutes to reach the death phase, while for many animal viruses it can exceed 24 hours before maximum titers are reached.

Figure: A typical ‘one-step’ growth or replicative cycle of a virus.

The replication cycles of five medically relevant human viruses have been selected to illustrate the similarities and differences of the key stages and various strategies of virus replication. Herpes simplex virus (HSV ) and human papillomavirus (HPV ) are both Class I viruses, poliovirus is of Class IV, influenza virus from Class V, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV ) is a Class VI virus. Their strategies are generally representative of similar viruses in each class but many variations occur.