Efficiencies of competitive equilibrium:

We now turns to three important efficiencies generated by the free market when on equilibrium, viz., (i) productive efficiency, (ii) allocative efficiency and (iii) product-mix efficiency.

Productive (Technical) Efficiency

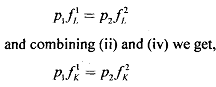

Productive efficiency requires that we cannot produce more of a good without producing less of another. In order to appreciate its underlying idea, we may have to recall the concept of opportunity cost. That is, the cost of producing more X can be readily measured by the reduction in Y output. Let us consider the marginal conditions described in (i) - (iv). Combining (i) and (iii) we get,

This means when we consider economic efficiency, marginal revenue product of labor (and capital) must be the same in both the industry. This mechanism is analogous to Smith invisible hand mechanism, which says that if the above two relationships do not hold, there will be competitive bidding among the employers in the concerned industries such that the equality will again be restored.

It can be proved that A, is the imputed value of labor and A, is the imputed value of capital. Thus, we can use above two Lagrange multipliers as proxy for wages and rent respectively. Then, from (i) and (ii), we get

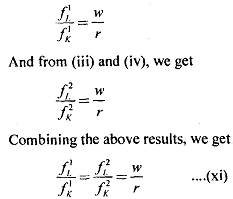

that is, the sector equates the ratios of marginal productivities cf factors to the price ratio and these ratios are equated across sectors. Consequently, we can say that productive (technical) efficiency is satisfied in the equilibrium. We can explain the above result using the Edgeworth Box diagram.

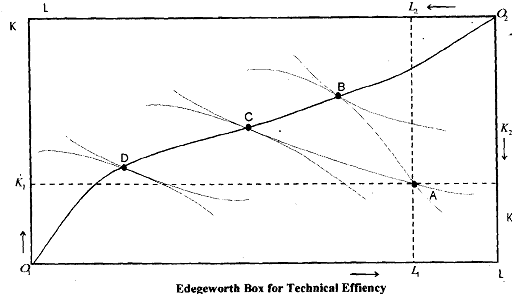

Figure shows the set of factor allocations in production for which Pareto efficiency is achieved. (By Pareto efficiency we mean no further gains from trade can be obtained if one moves from the above allocation. i.e., there is no mutually possible betterment if one move from a Pareto efficient allocation).

The X-axis and Y-axis of the box are total endowment of labor and capital respectively. Labor is plotted horizontally and capital vertically. With respect to the origin O1 we have drawn the isoquants for the first industry and with respect to the origin O2 we have drawn isoquants for the second industry. The efticient factor allocation consists of the points are those input combinations for which slopes of the isoquants for the two industries are equal. This condition is given by the equation (xi).

The curve O1 O2 is known as the efficiency locus or the contract curve, which is obtained by joining the points at which isoquants are tangent to each other.

Any point, which is off the curve, is inefficient in Pareto sense. For example consider the initial endowment point A. Movement form A to points B or C (both of which are on the contract curve will lead to increase in output for at least one industry while the output of the other industry will remain constant. Thus, there is scope for mutual betterment if the allocation point is off the contract curve. At all points on the contract curve, all possible gains fiom trade are exhausted. The efficiency locus will be obtained through the above invisible hand (i.e., bargaining) mechanism if there is no transaction cost involved in the process of bidding. It is to be noted that every point on the contract curve corresponds to a point on the production possibility frontier. Thus, the production possibility'frontier is one to one mapping of the contract curve from the input space to the output space.