Oxides

Oxygen creates binary compounds with almost all elements. Most of them may be obtained through direct reaction, even though other methods (like the thermal decomposition of carbonates or hydroxides) are occasionally more convenient. Oxides may be generally classified as ionic, polymeric or molecular. Covalent oxides are created with nonmetals, and may consist of terminal (E=O) or bridging (E-O-E) oxygen. Particularly strong double bonds are created with C, N and S. Bridging is more familiar with heavier elements and leads to the formation of several polymeric structures like SiO2.

Most abundant molecular substance on Earth is the water H2O. It is highly polar, with physical properties conquered through hydrogen bonding and an excellent solvent for ionic reactions and substances. Several hydrated salts are known (example CuSO4.5H2O), that contain water bound through coordination to metal ions and/or hydrogen bonding to anions. Autoprotolysis provides the ions H3O+ and OH-, that are also known in solid salts, H3O+ with anions of strong acids (example [H3O]+[NO3]-; hydrated species like [H5O2]+ are also known), and OH- in hydroxides, which are created through several metals.

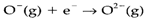

Oxides of several metallic elements have structures which may be generally classed as ionic. The closed-shell O2- ion is not known in the gas phase, the reaction

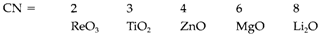

being extremely endothermic. So it is only the large lattice energy get with the O2- ion that stabilizes it in solids (see Topic D6). The range of coordination numbers (CN) of oxide is large, instances being:

Oxide has a remarkable trend for symmetrical coordination in ionic solids (linear, planar or tetrahedral with CN=2, 3 or 4, correspondingly) and different from the sulfide seldom forms layer structures.

The distinction among polymeric and ionic solids is not absolute and oxides of metals with low electropositive character (example HgO) or in high oxidation states (example CrO3) are better explained as having polar covalent bonds. A few metals in extremely high oxidation states form molecular oxides (example Mn2O7, OsO4).

Several ternary and more complex oxides are well known. It is general to differentiate complex oxides like CaCO3, that consist of discrete oxoanions, and mixed oxides like CaTiO3, that do not.

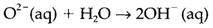

In water, the extremely basic O2- ion reacts to create hydroxide:

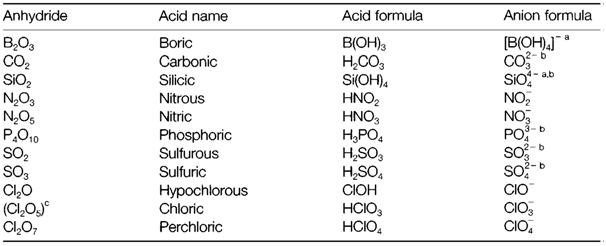

Table 1. Some oxoacids, showing their anhydrides and the anions formed by them

aAnion with a strong tendency to polymerize and create complex structures.

bPolyprotic acid along with intermediate states of ionization possible.

cParent anhydride unknown.

and thus ionic oxides are basic and if soluble in water, either form alkaline solutions, or else dissolve in acid solution. Covalent oxides (including those like CrO3 formed through metals in high oxidation states) are acidic and react with water to create oxoacids:

So such type of oxides may be regarded as acid anhydrides. Table 1 depicts a selection of oxoacids with their anhydrides and demonstrates the conventional nomenclature. For instance, sulfuric and sulfurous acids show the higher (+6) and lower (+4) oxidation state, correspondingly and their anions are called sulfate and sulfite.

Some oxides are amphoteric and comprise both acidic and basic properties; this frequently occurs with a metal ion with a high charge/size ratio like Be2+ or Al3+. Some nonmetallic oxides (example CO) are neutral and have no considerable acid or basic properties.