Touch

Have you still felt the touch of someone’s hand on your shoulder and establish yourself letting go of tension you didn’t even know you were holding? We can perhaps all memorize the impact a touch has had on us, whether relaxed or in a therapeutic setting. As practitioners, we have daily occurrences of the effects of touch on our clients. Present research in neuroscience is looking directly at the brain’s reaction to touch. Lucy Brown, a neuroscientist concerned in learning alternative therapies, presented latest findings at a talk at Harvard Medical School. What follows is mainly my abstract of her talk with a few comments from the point of view of a practitioner.

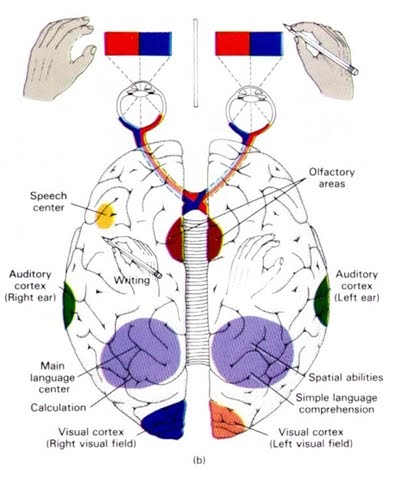

Whenever touch signals reaches the brain, at that point signals are pre-sorted, by the nature of the receptors, for cold, pain, and the like, and for intensity by the speed at which the nerves fire. Now starts the integration.

Underneath each cell group of the homunculus are a set of columnar brain structures similar to those explained for hearing, although devoted to touch. Here, as a signal moves deeper in its column, it becomes more accurate--the brain identifies edges and motion, for illustration, as the visual system does--although also more abstract and complicated to study. (A neurological code for edgeness wouldn't essentially look like an edge, for illustration.) Coded impulses fan out to another portion of the brain, becoming more and more enigmatic.