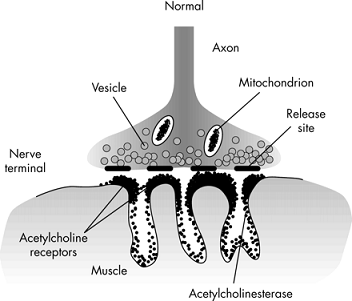

Nerve–muscle synapse

In neuromuscular junction, the point at which the motor nerve fiber invaginates the muscle fiber is known as the endlplate. The transmission of neuronal impulse across the synaptic cleft is made possible via the secretion of an acetylcholine. As the stimulus reaches to muscle fiber, cholinesterase is also secreted, that deactivates the acetylcholine by chemically breaking it down. This avoids further excitation of the muscle fiber following stimulation for that instant time period.

The way in which a stimulus is transmitted from the nerve to the muscle fiber is very alike to the manner in which an impulse is transmitted from nerve to nerve through the neuronal synapse. Actually, the main difference is that there is no inhibition mechanism at the neuromuscular junction. The muscle fiber receives only one nerve fiber. Though, the large fibers of an efferent nerve divide into several smaller fibers servicing as many as 200 muscle fibers. A separate nerve fiber plus all the muscle fibers it innervates is known as a motor unit. As an impulse appears at the neuromuscular junction, acetylcholine is discharged; the impulse is then able to cross the synapse, generating a potential in the muscle fiber. Such a potential, is known as excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP). The motor neuron activating the muscle fiber might receive impulses from numerous nerve fibers. When the postsynaptic potential is too small then the muscle fiber will not contract; but whenever the EPSP rises to a certain level, discharge occurs and the muscle fiber contracts. All or not anything.

This progressive increase in the size of the EPSP as an outcome of a number of impulses is known as spatial summation. Additionally, successive discharges from the similar postsynaptic terminal will summate eliciting an increased EPSP, given that the discharges take place in rapid succession. As before, this mechanism is known as temporal summation.

By inhibiting activation of brain cells, anesthetics, sleep, and too much alcohol avoid sufficient stimulation of recipient neurons.In conclusion, motor units receive impulse volleys at a rate which relates to the makeup of their constituent fiber kinds with an overall range between around 10 and 60 Hz. It is not astonishing that these reports would point to a higher rate of firing whenever more force is being applied.