Application: Money Growth and Hyperinflations

In the low inflation countries there is debate about the best policy, but in some countries there is little doubt that a constant growth rate rule is better than what they have. In the last decade, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Israel have experienced hyperinflation situations (situation of very high rates of inflation). Russia in the nineties also experienced very high rates of inflation. We can confidently expect several more over the years.

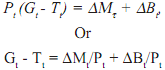

But why did it happen? If the relation between money growth and inflation is so clear, why don't these countries simply print less money? If only it were so easy! The real problem most of these countries have had was a large fiscal deficit. Let's think how that influences monetary policy. If a government is running a deficit, then it must issue IOU's of some sort to pay for it. Roughly, speaking, they may issue money (rupee notes or their local equivalent) or interest-bearing debt (treasury bills and notes) denoted with the B. Mathematically we can express this as

where the two terms on the right are issues of new money (ΔM) and new interest- bearing debt (ΔB), respectively. This is an example of a government budget constraint: it tells us that what the government doesn't pay for with tax revenues, it must finance by issuing debt of some sort.

So why do these countries increase the money supply? The problem, typically, is that a political impasse makes it nearly impossible to reduce the deficit. Given the government's budget constraint, it must then issue debt. Now for OECD countries' debt there is apparently no shortage of ready buyers, but the same can't be said for Argentina, Brazil, or Russia and many other developing countries. If they can't issue debt and they can't reduce the deficit, the only alternative left is to print money and the only option to raise resources: in short, when they can't pay their bills any other way, they pay them with money, which is easy enough to print. The effect of this, of course, is that these countries experience extremely high rates of inflation. Note that whenever a central bank prints "fresh money" it can obtain goods and services in exchange for these new pieces of paper. The amount of goods and services that the government obtains by printing money in a given period is called "seignorage". In real terms, this quantity of goods and service is given by the following expression:

Seignoraget = ΔMt /Pt = New bills printed in period t/Price level during period t.

The monetary aggregate that the central banks control directly is the "monetary base" consisting of currency in the hands of the public and reserves of the commercial banks deposited in the central bank. Thus, when we refer to a central bank as "printing more money", we mean increasing the monetary base.

Note that since the government, by printing money, acquires real goods and services, seignorage is effectively a tax imposed by the government on private agents. Such a seignorage tax is also called the inflation tax. The reason is the following. From the definition of seignorage:

Seignoraget = ΔMt /Pt = (ΔMt /Mt ) (Mt /Pt )

Since the rate of growth of money (ΔM/M = m) is equal to inflation (p) (assuming, for simplicity, that the rate of growth of output y is zero), we get:

Seignoraget = pt(Mt /Pt)

In other terms the inflation tax is equal to the inflation rate times the real money balances held by private agents. This makes sense: the inflation tax must be equal the tax rate on the asset that is taxed times the tax base. In the case of the inflation tax, the tax base is the real money balances while the tax rate at which they are taxed is the inflation rate. In other terms, if I hold for one period an amount of real balances qual to Mt /Pt , the real value of such balances (their purchasing power in terms of goods) will be reduced by an amount equal to pt (Mt /Pt) after one period. The reduction in the real value of my monetary balances caused by inflation is exactly the inflation tax, the amount of real resources that the government extracts from me by printing new money and generating inflation. Some claim that inflation is actually a 'fiscal' phenomenon. To understand better why inflation is a fiscal phenomenon, note again that a government with a budget deficit can finance it either by monetizing it (i.e. by printing money - that leads to seignorage or the inflation tax) or by issuing public debt:

P (G-T) = ΔM + ΔB = p (M/P) + ΔB

Note also that countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Israel had very high inflation rates in the 1980s. Now, if inflation was purely a monetary phenomenon caused in the first place by an exogenous excessive rate of growth of money,these countries could have reduced inflation quite fast by printing less money and reducing the growth rate of the money supply. Instead, all these countries had a really hard time in reducing their inflation rates. So, if inflation was due to an exogenous high growth rate of money, why didn't these countries print less money? The main problem was that these countries had large structural budget deficits and printed money to finance it. In this sense, the excessive growth rate of money that led to seignorage and caused inflation was not exogenous but rather endogenous and caused itself by the need of these governments to finance their budget deficits.

Note, however, that these countries could have in principle avoided the high inflation if they had cut their budget deficits (thus reducing the need for seignorage revenues) and/or if they had financed their budget deficits by issuing bonds rather than by printing money. This leads to the further question: why weren't the deficits reduced and/or why weren't the deficits financed by issuing bonds?