Virus-Structure

Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that only show activity within the cells of living organisms. All life on earth – plant, animal, bacterial, fungal – plays host to one or more viruses and in order to persist in the environment viruses must be capable of being passed from host to host and of infecting and replicating in susceptible host cells. Viruses cannot be viewed with a light microscope due to their small size; they range from approximately 20 to 400 nm, although some filoviruses can reach lengths of over 1000 nm. A virus particle can be defined as a structure that has evolved to transfer genetic information (nucleic acid) from one cell to other. The nucleic acid found in the particle is either DNA or RNA, and may be single- or double-stranded, linear or circular, intact or segmented.

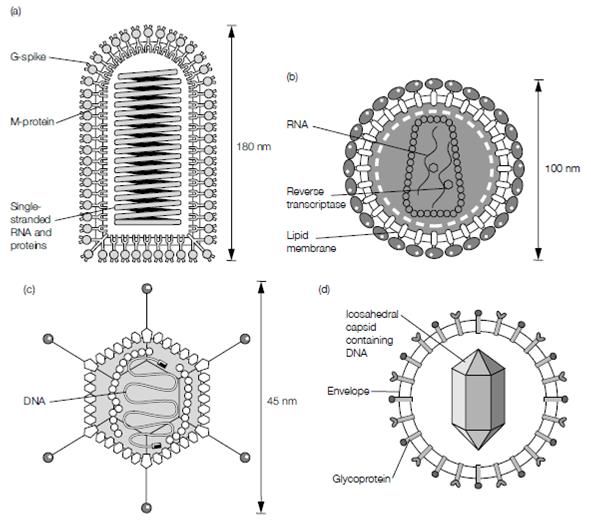

The easiest of virus particles consists of a protein coat (sometimes made up of only one type of protein, repeated hundreds of times) surrounding a strand of nucleic acid. A protein coat surrounding the nucleic acid is referred to as the capsid and is composed of proteinaceous units or capsomers. The category of capsomer depends on the overall shape of the capsid but in the case of icosahedral capsids the capsomers are either pen- tamers or hexamers. Capsomers themselves consist of subunits often called protomers, which are a collection of one or more nonidentical protein subunits that bind together to form the building blocks for capsomer and capsid assembly (e.g. virus proteins VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 of picornaviruses). Within the capsid lies the nucleic acid genome of the virus, which may exist in a nucleic acid–protein complex known as a nucleocapsid, often referred to as the core of the virion. While some authors use these structural terms inter- changeably, the distinction between nucleocapsid and capsid should be appreciated.

The protein coat of more complex viruses is further surrounded by a membrane, the envelope, usually derived from modified regions of a cellular membrane as the virus escapes the infected cell. The envelope has peplomers (projections) formed of virally encoded glycoproteins, that are visible as a ‘fringe’ around the virion when viewed with an electron microscope The space between the capsid and envelope is not empty; it too contains virally encoded proteins and is referred to as the matrix or (when describing herpesviruses) the tegument.

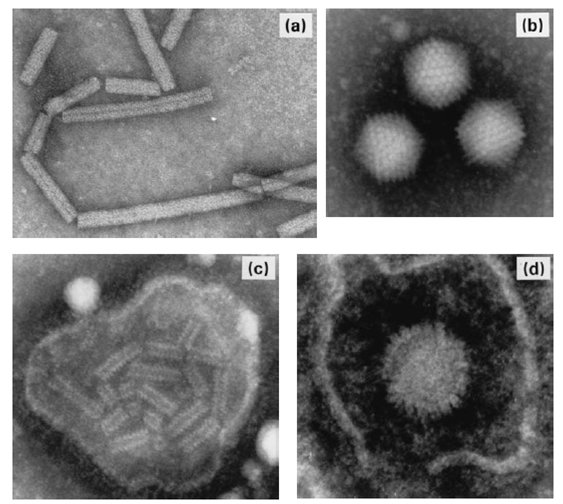

Figure: Examples of viruses from main groups according to ‘standard’ morphology (a) unenveloped/helical (tobacco mosaic virus); (b) unenveloped/icosahedral (adenovirus); (c) enveloped/helical (paramyxovirus); (d) enveloped/icosahedral (herpesvirus).

Figure: Diagrammatic representation of the structure of four virus particles. Rabies virus (a) and HIV (b) have tight-fitting envelopes; herpes simplex (d) has a loose-fitting envelope, whereas adenovirus (c) is nonenveloped. The diagrams are based on electron microscopic observation and molecular configuration exercises.