Inefficient Provision of Public Goods:

Suppose we have a public good but we can exclude people from using it. Remember that it does not involve extra cost to let someone use a public good (e-g., a park). If we try to charge people to let them in and set the price higher than what is worth to the least park-liking person, then we end up with an inefficient outcome. Any price that results in the exclusion of a visitor is too high since all people benefit from the park. Since we cannot charge an entry fee, and therefore, we have to collect the resources for it in some way that does not discourage its use. We can charge different prices to different people, but that is there is a need to devise some pricing scheme where people would correctly reveal how much the park is worth to them. However, it is very difficult to get people to reveal what a public good is worth them.

The non-rival nature of public good consumption has important bearing on (I) what constitutes efficient resource allocation, i.e., allocation of resources to produce at least cost what consumers want most, and (2) the procedure by which their provision is to be achieved. These implications will now be examined'more carefully when we compare it with the provision of private

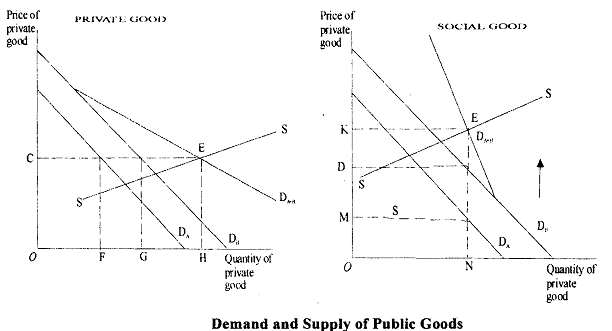

goods as shown in the figure below.

To explore problem 1, it is helpful to compare the familiar demand and supply diagram for private goods with a corresponding construction for public goods, as they would compare in a hypothetical market setting. The latter, as we will see presently, is unrealistic, but it is nevertheless useful in noting essential differences between the two situations. The left side of Figure 16.8 shows the conventional market for a private good. DA and DB are A's and B's demand curves, based on a given distribution of income and prices for other goods. The aggregate market demand curve DA + B is obtained by horizontal addition of DA and DB, adding the quantities which A and B purchase at any given price. SS is the supply schedule, and equilibrium is determined at E, the intersection of market demand and supply. Price equals OC and output OH, with OF purchased by A and OG by B, where OF + OG = OH. The right side of the figure shows a corresponding pattern for a public good. We assume for this purpose that consumers are willing to reveal their marginal evaluations of the public good-say, weather forecasting installations-it being understood that daily reports will be available free of charge. As before DA and DB are A's and B's respective demand curves, subject to the same conditions of given incomes and prices for other goods. Since it is unrealistic to assume that consumers volunteer their preferences, such curves have been referred to as "pseudo-demand curves." But suppose for argument's sake that consumer preferences are revealed. The critical difference from the private-good case then arises in that the market demand curve DA + B is obtained by vertical addition of DA and DB, with DA + B showing the sum of the prices which A and B are willing to pay for any given amount. This follows because both consume the same amount and each is assumed to offer a price equal to his or her true evaluation of the marginal unit. The price available to cover the cost of the service equals the sum of prices paid by each. SS is again the supply schedule, showing marginal cost (chargeable to A and B combined) for various outputs of the public good.

The level of output corresponding to equilibrium output OH in the private- good case now equals ON, which is the quantity consumed by both A and B. The combined price equals OK, but the price paid by A is OM whereas that paid by B is OL, where OM + OL = OK Returning to the case of the private good, we see that the vertical distance under each individual's demand curve reflects the marginal benefit, which derives from its consumption. At equilibrium E, both the marginal benefit derived by A in consuming OF and the marginal benefit derived by B in consuming OG equals marginal cost HE. This is an efficient solution

because marginal benefit equals marginal cost for each consumer. If output falls short of OH, marginal benefit exceeds marginal cost and individuals will be willing to pay more than is needed to cover cost. Net benefits will be gained by expanding output so long as the marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost of so doing, and net benefits are therefore maximised by

producing OH units, at which point marginal benefit equals marginal cost.

Welfare losses would occur were output expanded beyond OH, for marginal cost would thereby exceed marginal benefits. Let us now compare this solution with that for public goods. While the vertical distance under each individual's demand curve again reflects the marginal benefits obtained, the marginal benefit generated by any given supply is obtained by vertical addition. Thus, the equilibrium point E now reflects the equality between the sum of the marginal benefits and the marginal cost of the public good. If output falls short of ON, it will again be advantageous to expand because the sum of the marginal benefits exceeds cost. An output in excess of ON, on the contrary, would imply welfare losses, since marginal costs outweigh the summed marginal benefits. Thus the two cases are analogous but with the important difference. For the private good, efficiency requires equality of marginal benefit derived by each individual with marginal cost. In the case of the public good, on the other

hand, the marginal benefits derived by the two consumers differ and it is the sum of the marginal benefits (or marginal rates of substitution) that should equal marginal cost.

The figure also shows that an application of the same pricing rule where the price payable by each consumer equals the individual's marginal benefit yields different results for public and private goods. In the private-good case, A and B pay the same price but purchase different amounts, whereas in the public good case, they purchase the same amount but pay different prices. Yet in both cases, the same pricing rule is applied. Each consumer pays a single price for successive units of the good purchased, with the price equal to the marginal benefit that the purchaser derives.