Battery expansion:

The idea that you may get is that you can connect hundreds, or thousands, of batteries in series and retain batteries with fantastically high EMFs. Why not put 1,000 zinc-carbon batteries in series, for that instance, and get 1.5 kV? Or put the 2,500 solar cells in series and obtain 1.25 kV? Maybe it is possible to put the billion solar cells in the series, out in some vast sun scorched desert wasteland, and use the resulting 500 MV to feed the biggest high tension power line.

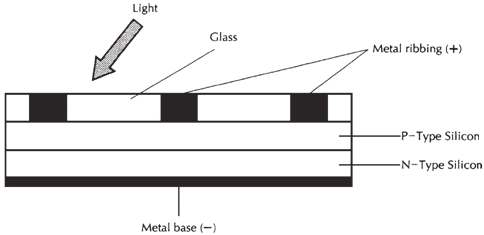

Figure: Cross-sectional view of silicon photovoltaic (solar) cell construction.

There are many reasons why these schemes are not good ideas. First, high voltages for practical purposes is generated efficiently by power converters which work from 117-V or 234-V utility mains. Second, it could be hard to maintain a battery of thousands, millions or billions of cells in the series. Imagine a cell holder having 1,000 sets of contacts. And not one of them can open up, lest the whole battery become ineffective, as all the cells should be in series. Solar panels, at least, can be permanently wired together. Not so with the batteries that should often be replaced. And the internal resistances of the cells would add up and restrict the current, as well as the output voltage, which could be derived by connecting many cells in series. This is not so much of a problem with the series parallel combinations, as in solar panels, as the voltages are reasonable. But it is a big factor if all cells are in series, with intent of getting a huge voltage. This effect will happen with any type of cell, whether photovoltaic or electrochemical.

At the time of Second World War, portable two-way radios were built by using vacuum tubes. These were charged by batteries supplying 103.5 V. The batteries were many inches long and about an inch in diameter. They were prepared by stacking many little zinc-carbon cells on top of each other, and enclosing the whole assembly in the single case. They were dangerous; a fresh 103.5-V battery would light up a 15-W household incandescent bulb to full brilliance. But the 117-V outlet would work better, and for much longer.

Nowadays, handheld radio transceivers will work from NICAD battery packs or batteries of ordinary dry cells, giving 6 V, 9 V, or 12 V. Even the biggest power transistors use higher voltages rarely. Automotive or truck batteries can produce enough power for almost any portable communications system. And if a really substantial setup is needed, gasoline-powered generators are available, and they will supply the required energy at far less cost than batteries. There is no use for a mega- battery of a thousand, a million, or a zillion volts.