Scitovsky Reversals and the Double Criteria:

Not only the strong Kaldor criteria is unable to compare various allocations consistently, but also there are problems regarding the weak Kaldor criteria for comparisons of welfare under different types of change. The famous Scitovsky reversal paradox, first identified by Tibor Scitovsky, uncovered an important drawback of the weak Kaldor criterion. Scitovsky pointed out that if some situation position, say B, is shown to be an improvement over position A on Kaldor-Hicks criterion, it may be possible that position A is also shown to be an improvement over B on the basis of same criterion. For getting consistent results when position B has been revealed to be preferred to position A on the basis of a welfare criterion, then position A must not be preferred to position B on the same criterion.

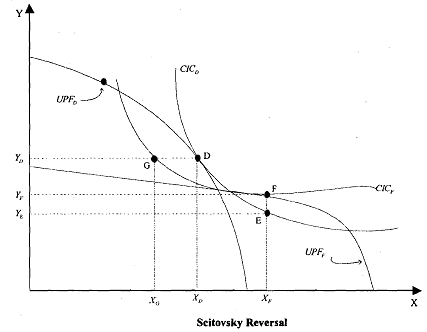

Suppose in a production economy, the production conditions change due to change in technology. This will lead to the shift of the position and as a result the move from PPFD to PPFF. In order to judge whether this technological change improved or worsened welfare, the corresponding Pareto-optimal points D and F represented by the tangencies of CICD with PPFD and CICF with PPFF can be compared.

It can be seen that CICD and CICF intersect each other, which implies that intersecting CICs imply Pareto-improvements. This means that F is Pareto- superior to E. Moreover, E represents the same level of "aggregate" utility as D as they are on the same CICD. Thus, from D, it is possible to hypothetically redistribute goods and outputs so that we obtain a Pareto-improvement.

According to the weak Kaldor criteria, situation F is superior to D. However, by a reverse argument, it can be seen that as a result of the movement from PPFF to PPFD, D is Pareto-superior to G and G yields the same level of "aggregate" utility as F as it lies on CICF. Thus, by the weak Kaldor criteria again, situation D is ranked higher than that of F. There is a "reversal" of

rankings between D and F by the weak Kaldor criteria as F is better than D and D is better than F.

Therefore, Scitovsky suggested that resolution to this reversal paradox might be done by combining both the Hicks and Kaldor criteria. This is explained in the figure above. As can be seen from the figure, the movement from D to F fulfills the Kaldor criteria but not the Hicksian one, asfiom D, it is possible to undertake hypothetical lump-sum redistribution within PPFD that achieves a Pareto-improvement over F (e.g., a point slightly above G in PPFD is a Pareto- improvement over G and thus over F). The Scitovsky double criteria state that an allocation is preferred to another if it fulfills both the Kaldor and Hicks criteria. This would, it seems, eliminate Scitovsky reversals as that depicted in Figure above. Thus when the two utility possibility curves are non-intersecting and change involves movement from a position on a lower utility possibility curve to a position on a higher utility possibility curve, the change raises social welfare on the basis of the Kaldor-Hicks-Scitovsky criterion. This occurs only when a change brings about increase in aggregate output or real income.