Bioluminescence

Many of the marine dinoflagellates are capable of bioluminescence, where chemical energy is used to generate light. The light is in the blue–green range, 474 nm, and can be emitted as high-intensity short flashes (0.1 second) either spontaneously, after stimulation, or continuously as a soft glow.

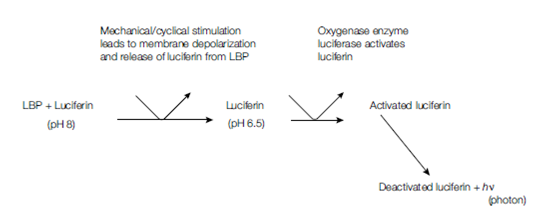

Bioluminescence is created by the reaction between a tetrapyrrole (luciferin) and an oxy- genase enzyme (luciferase). The entire reaction is held within membrane-bound vesicles called scintillons, where the luciferin is sequestered by luciferin-binding protein (LBP) and held at pH 8. Release of light is stimulated by either a cyclical or mechanical stimula- tion of the scintillon, which leads to pH changes within it. Luciferin is released from LBP, and luciferase is able to activate it. Activated luciferin exists for a very brief time before it returns to its inactivated form, releasing a photon of light energy.

The distribution of scintillons within the photosynthetic cell varies over 24 hours. During the night they are distributed throughout the cytoplasm, but in daylight they are tightly packed around the nucleus. The function of bioluminescence for the organism is uncertain. It appears to be useful in defense against predators. It has become important in medicine and science because the coupled system of luciferin/luciferase can be used to mark cells. Once tagged with the bioluminescent marker, marked cells can be mechanically sorted from other cells, visualized by microscopy or targeted for therapy.

Figure: Luciferin–luciferase reaction within scintillon. LBP, luciferin-binding protein.