Methods of cell culture

Eukaryotic cells can be cultured in the laboratory in sterile glass or plastic flasks of various sizes or in large vessels or vats (known as fermenters) for large-scale purposes. It is essential to keep the cultures free of fungal and bacterial contamination that would otherwise outgrow the cells as a result of the rich media used, destroying them. Although several antibacterial and antifungal additives are available, the primary barrier to contamination must be constant and vigilant aseptic technique. Reagents and equipment for use in cell culture must also be sterilized, by autoclaving (moist heat), hot-air ovens (dry heat), membrane filtration or, in the case of plastic ware, irradiation.

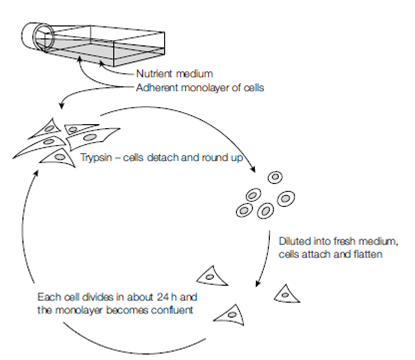

Once a cell line is established, it must be maintained regularly by a process known as sub- culturing (often called passaging, splitting or feeding the cells). Cells are harvested from the culture vessel and gently homogenized to obtain a single-cell suspension, which can then be counted, allowing a known concentration of cells to be seeded into a new sterile flask along with the appropriate liquid medium (plural = media). The flask (a plastic or glass bottle-like container) is incubated at the appropriate temperature, usually 37?C for mammalian cells. For adherent cells, the flask is incubated lying on one side and the cells attach to the inner surface of the flask wall; modern plastic culture flasks have a chemical coating to help rapid and secure adherence of cells. Once attached to the vessel wall, the cells begin to metabolize the available nutrients and soon begin to divide, forming a monolayer of cells over several days. The metabolic activity of the cells means that the medium will eventually be depleted of nutrients, the levels of metabolic waste products will rise, and the available surface for cell adherence will be filled (the monolayer is said to be confluent). These conditions are inhibitory to mitosis and, unless subcultured again, the cells will deteriorate and die. The monolayer is treated with trypsin or versene, which breaks the protein bonds that allow cell adherence to the flask and the processes described above are repeated. In addition to culturing in flasks (for long-term maintenance of the cell line and virus propagation), smaller cell monolayers can be established temporarily in the wells of specially designed multi-well culture plates, which allows for experimental infections examining virus replication, biology, and host cell interactions. More recently, there has been a move to encourage some cell types to grow in suspension, where cells do not anchor themselves to the surface of the flask or adhere to each other (e.g. hybridoma cells which secrete monoclonal antibodies).

Two natural phenomena restrict cell mitosis in vitro. Most cell lines exhibit contact inhibition whereby they suspend mitosis when in contact with surrounding cells, meaning that a monolayer remains static once it has reached confluence. The process of sub- culturing dilutes the cells into fresh vessels, giving them space to continue mitosis and maintain the cell line. The second restriction is the natural lifespan of cells, which can only undergo a defined number of mitotic divisions (known as the Hayflick limit, this is approximately 50 divisions for human cells). This limited lifespan of cells inevitably imposes a defined lifespan on a cell line, after which it can no longer continue. To pre- serve the cell line it is usual to store samples of cells taken from an early subculture (e.g. at a passage number between 10 and 15) by freezing them in liquid nitrogen. This allows cells to be preserved in a metabolically inert, but viable, state and to be resurrected by rapid thawing and returning to a culture flask with medium once again. Cells that have been transformed (such as those derived from tumors) do not show these limitations. Without contact inhibition cells continue dividing, piling up on top of each other, after confluence has been reached. Transformed cells also have no apparent Hayflick limit,and hence a greatly increased (possibly limitless) mitotic lifespan. These are often known as immortal cell lines

Figure: Cell culture.