Market Failure Argument:

Our discussion on the merits of free trade was based on cost-benefit analysis using the concepts of consumer and producer surplus. However, under certain circumstances these concepts fail to accurately capture actual costs and benefits. This could happen for instance, in the presence of domestic market failures. A market failure occurs whenever markets fail to allocate resources optimally.

There can be several examples of domestic market failures. For instance, the presence of unemployment clearly indicates that the labour market is not clear- ing. Structural rigidities in capital or labour markets may prevent resources from being transferred rapidly to sectors yielding highest returns, resulting in inefficient resource allocation.

In the presence of market failure, producer surplus would not properly measure the benefits of producing a good. In this case, if resources are unemployed, their private costs to employers exceeds their opportunity cost to society. This means that private firms will produce such goods a level that is less than what is optimal for society.

Externalities are another type of market failure. For example, a new technique developed in a certain sector may potentially improve the technology of the economy as a whole. However if firms producing this good do not directly benefit from the economy-wide application of their technology, they do not take this 'potential gain' into account while deciding how much to produce.

This is what we call a positive externality. In this case the producer surplus fails to capture the marginal social benefit of additional production. This implies that the government should institute some policy that encourages firms to expand their output.

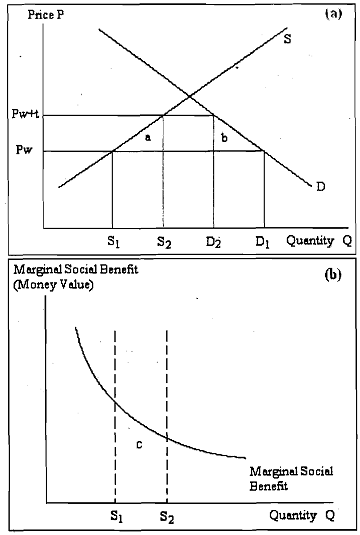

The existence of marginal social benefit can be used as a justification for adopting.protectibnist trade policies. protectionism. Figure (a) shows the conventional cost-benefit analysis of a tariff. It applies to a small country, which takes international prices as given -i.e., terms of trade effects of the kind discussed above, are ruled out. Figure (b) shows the marginal social benefit from production, not captured in the producer surplus. You should study these two figures carefully. Note that a tariff on imports, raises the domestic price of the importable from Pw to Pw + t (Figure (a)), reduces domestic consumption (from D, to D2) and raises production (from S to S2).

In terms of the conventional mea- sures of consumer and producer surplus, the sum of the triangles a and b measures the net (Figure (a)) loss to society from these distortions in production and consumption. However, the increase in production kom S, to S2 yields an additional social benefit. This is measured by the area c under the marginal social benefit curve between Sl and S2 (Figure (a)). Taking this into account, the benefits of the tariff may exceed its associated costs. In fact. it can be shown that for a small enough tariff rate, the social benefit of a tariff c, would always exceed its costs measured by the area (a + b). Also it can be proved that there is some welfare-maximising tariff rate that yields a higher level of social welfare as compared to free trade,-making protection preferable to free trade.

The domestic market failure argument for protectionism is a particular case of a more general concept in economics known as the theorv of the second best. This theory provides a justification for government intervention in a given market;in order to correct a market failure in a second market. The domestic market failure argument for protection amounts to applying the theory of the second best to trade policy. In this case internal market imperfections justify the adoption of trade policies affecting the external sector. Thus, even when international trade is not the source of the problem, trade policy measures can provide at least a second best solution.

There are at least a couple of limitations to using the domestic market failure argument as a justification for trade protection. First, note that trade policies are second-best policies for dealing with the problem of domestic market failures. Ideally such market failures should be i, corrected directly using first-best domestic policies. For, second best policies I are inefficient, as they create distortions and lead to welfare losses. Very often first-best policies appear too costly, while the costs of second-best policies are far less apparent.

For example, using Figure (a) and (b) above we showed that the social welfare of a tariff would exceed costs when there are significant social benefits 'from increased production. However, note that the same increase in production could have been effected by a domestic policy, viz. a production subsidy. With a subsidy, the price paid by consumers would not have increased and thus the loss b, associated with a tariff could have been avoided. A second critique of the domestic market failure argument relates to the fact that in reality market failures are hard to identify precisely and it is difficult to be sure about the most appropriate policy response to correct the problem.