Gravity model:

One alternative explanation to trade theory came from what is known as the social physics school of thought in economics. The gravity model of trade that used the gravity theory of Newton in physics mainly represented the alternate trade-determinants.

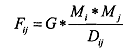

The gravity model of trade in international economics, similar to other gravity models in social science, predicts that bilateral trade flows are based on the economic sizes (often using GDP measurements) and distance between two units. The model was first used by Jan Tinbergen in 1962. The basic theoretical model for trade between two countries (i and j) takes the form of:

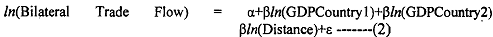

Where F is the trade flow, M is the economic mass (or GDP) of each country, D is the distance and G is a constant. Taking logarithms, we can convert the equation (1) into a linear form for econometric analysis where constant G becomes a as shown in equation (2)

The model often includes variables to account for income level (GDP per capita), price levels, language relationships, tariffs, contiguity, and colonial history (whether Country1 ever colonised Country2 or vice versa). The gravity model estimates the pattern of international trade. While the model's basic form consists of factors that have more to do with geography and spatiality, the gravity model has been used to test hypotheses rooted in purer economic theories of trade as well.

Using the gravity model, countries with similar levels of income have been shown to trade more. Helpman and Krugman see this as evidence that these countries are trading in differentiated goods because of their similarities. This casts some doubt about the impact Heckscher-Ohlin has on the real world.

The gravity model estimates the pattern of international trade. While the model's basic form consists of factors that have more to do with geography and spatiality, the gravity model has been used to test hypotheses rooted in purer economic theories of trade as well. Using the gravity model, countries with similar levels of income have been shown to trade more. Helpman and Krugrnan see this as evidence that these countries are trading in differentiated goods because of their similarities. This casts some doubt about the impact Heckscher-Ohlin has on the real world.