Economies of scale:

Another important determinant of trade is economies of scale or increasing returns to scale in production. As you have learnt in micro economics, economies of scale mean that production at a larger scale can be achieved at a lower cost. When production within an industry has this characteristic, specialisation and trade can result in improvements in productive efficiency, competitiveness and welfare.

Trade between countries need not depend upon inter-country differences in the presence of economies of scale. It is possible that countries could be identical in all respects and yet find it advantageous to trade. Thus, presence of economies of scale is often used to explain trade between industrialised countries like the US, Japan and the European Union. When traditional models of trade failed to explain trade among these countries with similar technologies, endowments and similar consumer preferences, economies of scale could provide reasoning.

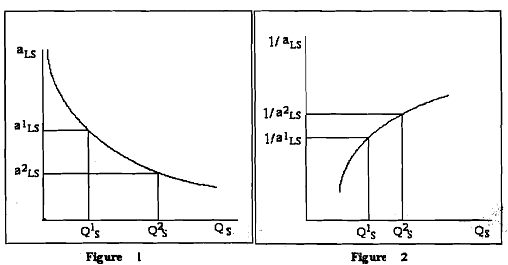

To reiterate, economies of scale in production mean that production at a larger scale (more output) can be achieved at a lower cost (i.e. with economies or savings). A simple way to formalise this is to assume that the unit-labow requirement in production of a good is a function of the level of output produced. In Figure 2.1 we present a graph of the unit-labour requirement in steel production as a function of the scale (level of output) of production. At production level Q1s the unit-labour requirement is given by a1LS. If production were to rise to Q2s then the unit-labour requirement would fall to a2LS. This means that at the higher level of output, it requires less labour (i.e. fewer re- sources or cost) per unit of output than it required at the smaller scale. With a simple adjustment it is possible to show that economies of scale in production are equivalent to increasing returns to scale. Increasing returns to scale in production means that an increase in resource usage, by say x%, results in an increase in output by more than x%. In the adjoining diagram we plot labour productivity in steel production when production exhibits increasing returns to scale. [This graph is derived by plotting the reciprocal of the unit-labour requirement (i.e. 1/a1LS) for each output level in Figure. Note that as output (scale) increases from Q1s to Q2s labour productivity (given by the reciprocal of the unit-labour requirement) also rises. In other words, output per unit of labour input increases as the scale of production rises, hence increasing returns to scale

Another way to characterise economies of scale is with a decreasing average cost curve. Average costs, AC, are calculated as the total costs to produce output Q, TC (Q), divided by total output. Thus AC (Q) = TC (Q)/Q. When average costs decline as output increases it means that it becomes cheaper to produce the average unit as the scale of production rises, hence economies of scale.

Economies of scale are most likely to be found in industries with large fixed costs in production. Fixed costs are those costs that must be incurred even if production were to drop to zero. For example fixed costs arise when large amounts of capital equipment must be put into place even if only one unit is to be produced and if the costs of this equipment must still be paid even with zero output. In this case the larger the output, the more the costs of this equipment can be spread out among more units of the good. Large fixed costs and hence economies of scale are prevalent in highiy capital-intensive industries such as chemicals, petroleum, steel, automobiles etc.