What is Interspecific Competition in ecology explain?

Populations in nature usually share their surrounding environment in time and space with populations of other species. If they rely upon the same resources, they may have to compete for them. Thus, the competition for resources between two or more species is referred to as interspecific competition. Competition for one or more resources could result in interactions that limit the size of a population, or populations.

A distinction is made between interspecific and intraspecific. The term interspecific refers to an interaction involving two different species, whereas intraspecific refers to an interaction that involves interaction between individuals of the same species.

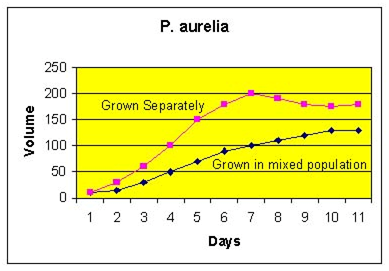

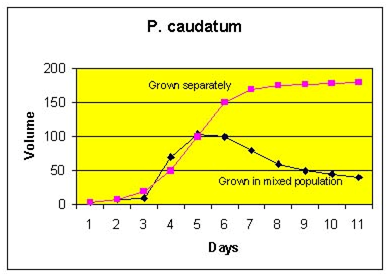

Experimental evidence from a scientist named Gause as early as 1934 demonstrated how the interaction of two species of Paramecium (microscopic ciliates) resulted in decreased population sizes. Gause grew two species Paramecium aurelia and Paramecium caudatum together and compared their growth to populations grown separately.

As you can see from the results, when grown separately, both P. aurelia and P. caudatum populations grow to much higher numbers than when grown together in mixed culture with a fixed amount of food resource. P. aurelia grows at a much faster rate, and thereby out competes P. caudatum. The P. caudatum population is reduced, and possibly could either face extinction, or be excluded from the area, were it a natural population. This led Gause to his conclusion that two species that have identical niches cannot occupy the same environment at the same time. This later came to be known as Gauses Principle of Competitive Exclusion.

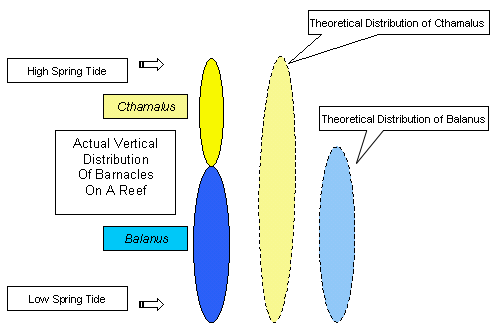

There are many examples of competitive exclusion at work in nature. Different species of barnacles inhabit different positions on the rocky shores along the coast of California. Experiments were carried out to determine the ranges of two species of barnacle, Cthamalus stellatus and Balanus balanoides. Balanus typically lives lower down on rocks in deeper water than Cthamalus, which grows further up on rocks in shallower water. J. H. Connell in an experiment, removed Balanus populations, allowing Cthamalus to extend down further and deeper. On the other hand, when he removed Cthamalus, Balanus did not move to occupy higher positions on the rocks.

A study of warblers conducted by R. MacArthur represents another well-known example of natural interspecific competition. He studied 5 species of warblers found in the northeastern U.S., which all feed on the same insects that lived typically in spruce trees. He asked the question: How do 5 different populations of different species co-exist without exclusion since they all partake of the same resource? The answer he found lay in what has come to be known as resource partitioning. Apparently each of the 5 species feed on different parts of the tree at the same time, reducing competition. One species fed on insects found in the interior reaches of tree branches, another fed at the top of the tree, another fed on the lower bottom branches, another species fed on mid-level inner branches, and the last species fed on the outer branches found at mid-height on the tree. In fact, the warblers filled different ecological niches, and therefore are able to coexist in the same environment at the same time.