The most basic version of a LIV allows the executive office holder (Governor or President) to accept part of a bill passed by the legislature (so that part becomes law) and to veto (or reject) other parts of the bill. Without LIV power,the executive can only accept or reject whole bill. Obtaining LIV power thus appears to

give a governor more power than he or she had previously.

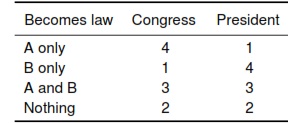

Dixit and Nalebuff ’s Thinking Strategically analyzes a situation like the following. Suppose that the U.S. President gets LIV authority. Suppose also that there are two distinct proposals (A and B) being debated in Washington. Congress likes proposal A; the President likes proposal B. These proposals are not mutually

exclusive; either or both (or none) may become law. There are thus four possible outcomes. The following table shows how the President and Congress rank the possible outcomes (where a larger number represents a more favorable outcome).

The timing of the game between the Congress and the President is that Congress (may) pass a bill, which is then sent on to the President for him either to accept or to veto, in full or (if possible) in part. If the President does not have LIV power, this game can be illustrated with the tree on the top of page 13;

with LIV power, with the tree below it.

(a) Enter the payoffs for Congress and for the President (in that order) for all of the possible outcomes of both versions of this game.

(b) Using backward induction, describe a rollback equilibrium of the no-LIV game.

(c) Using backward induction, describe a rollback equilibrium of the with-LIV game.

(d) In this situation has the additional power given by line-item-veto authority helped or hurt the President? In your own words, explain why.

(e) For whichever of the two outcomes is worse for the President, describe (in your own words) what he or she might do to improve that outcome.

(f) Suppose that outcomes were ranked in the way shown below. In this situation, would the President gain or lose from having LIV authority?

Solution:

|

Becomes law

|

Congress

|

President

|

|

A only

|

2

|

4

|

|

B only

|

3

|

1

|

|

A and B

|

4

|

3

|

|

Nothing

|

1

|

2

|

(b) Congress passes A and B together; the President signs the bill. Both A and B become law.

(c) Either Congress passes A only and the President vetoes it, or Congress passes nothing. Neither pro- posal becomes law.

(d) Hurt the president. Congress can’t count on him to sign the whole bill.

(e) The President could promise (see Chapter 9) to sign both bills. (f) LIV authority helps the President. With no LIV, A and B both become law. With LIV, only A

becomes law.