Economic Development and Health

The contribution of good health to improved growth and development prospects (or its opposite i.e. the contribution of poor health to reduced economic growth and development) is widely recognised. It is postulated in terms of:

(i) Nutrition links to labour productivity and growth;

(ii) Linkage between fertility and population dynamics to growth; and

(iii)Child and youth health links to growth.

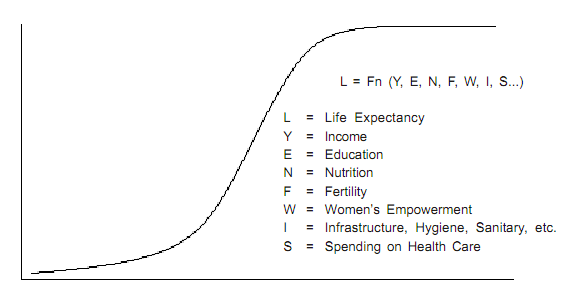

This is however not a one-way relationship as increase in wealth (via economic development and the resultant investment in health services) is considered good for health. In a study of cross-country regressions by Lant Pritchett and Lawrence Summers (1996), the authors demonstrate a strong causative effect between increased income and reduced infant mortality. Based on their analysis, they point out that if the developing world’s growth rate had been 1.5 percentage points higher in the 1980s, half a million infant deaths could have been averted. The history of modern economic growth since the early 19th century demonstrates that with growth, life expectancy has improved and infant mortality has declined. These indicators have improved due to an increased understanding of the causes of ill health, such as poor sanitation, as well as due to development of technologies (e.g. vaccines and antibiotics). Many diseases are not fatal, but disabling. The economic burden of such illnesses for the affected includes loss of income, and out-of-pocket expenditure on health. The economic burden for the country includes low productivity and the direct costs of treatment. During the second half of 20th century, the diffusion of technology and knowledge to low-income countries contributed to increasing the access to improved sanitary conditions and new medicines. This was possible due to increase in wealth without which the improved services could not have been afforded. Substantial improvements in health can occur even at low income levels. As a result of complex synergies among income levels and expenditure on education, better housing, clean water, sanitation systems, infrastructure, health services, etc., people all over the world live almost 25 years longer today than they did at similar income levels in 1900. However, it is equally important to note that the relationship between health and wealth is not linear.

With the attainment of a critical threshold, health gains will result even at low income levels. At such a point, even small increases in economic growth would result in high improvement in health outcomes. The importance of a synergy between the inter-sectoral programmes are underscored as they often improve the effectiveness of specific health programmes especially at low income levels. For example, investment in roads allow pregnant mothers to get to delivery services on time and vaccines to arrive at health centres without having the cold chain broken. Basic education is demonstrated to enable mothers to make the right choices when faced with health complications.

Impact of Wealth on Health (GDP/Capita)

Improved health can also promote economic growth through a demographic link.Though not directly obvious, shifts in demographic structure of a population can result by way of more children surviving to adulthood with a consequent increase in the proportion of economically active to dependent people. This ‘demographic dividend’ is contended to have the potential to be a key driver of economic growth provided the broader policy environment allows these workers to find productive employment. With such synergic achievement of intra-sectoral linkages, the changing age-structure of the population is expected to result in rapid increases in the per- capita income of the population. In East Asia, for example, between 1965 to 1990 the working age population grew several times faster than the dependent population. Several studies (e.g. Bloom and Williamson, 1998) have attributed this shift to the declining infant mortality brought about by the introduction of new health technologies such as antibiotics and anti-malarial drugs as well as general improvements in sanitation and clean water. The authors contend that these health improvements were responsible for as much as one-third of the region’s post-war economic growth.

Just as good health facilitates economic growth, poor health can severely constrain it. This is particularly true of the poor countries which typically have the greatest disease burdens. Most obviously, poor health can reduce economic development by reducing the quantity and the quality of labour available to an economy. This in turn reduces the number of hours worked impacting adversely on the national income generated. With such unhealthy trends continuing over a longer period, the rate of growth of an economy will be severely affected. Such weak growth trends, by extension, squeeze the amount of resources available with the government and individuals to invest on other essentials of progress viz. education, health, living conditions, etc. This would further exacerbate the vicious circle of poor health and poverty.