Karl Robinson is about to make his first major decision as president and chief executive officer of Conway Control & Instrument Corporation, a manufacturer of electronic test instruments and control systems for automated machine tools. The corporation was founded in 2000 by three former Compaq employees. The fledgling company's records of growth and profitability were extraordinary during the period 2000-2003, with earnings amounting to over $30 million in the third year of operation. Because investors assumed that this earnings trend would continue, the company's stock sold at approximately 20 times earnings during

2003, e.g., P/E ratio = 20, giving the firm a total market value of $600 million. At that point, each of the company's three founders held about 10 percent of the stock and had a paper net worth of approximately $60 million on an initial investment of about $60,000. The remaining

70 percent of the stock was owned by public stockholders, mainly mutual funds and bank pension trust managers.

The extraordinary expansion during the first three years of the new company's life was financed partly by the sale of stock now owned by the public and partly by bank credit. Most of the bank credit consisted of short-term loans used to finance computer equipment purchased "off the shelf" and integrated into the control systems leased to clients. Each client leased a package that included computer hardware and monitoring instruments plus machine control programs especially designed and written by Conway's programmers to meet the client's specialized needs.

The three founders made two mistakes. First, they put up their own stock in the company as collateral for personal bank loans that they used to buy the stock of other high technology companies. Second, Conway purchased a large quantity of computer modules just before the announcement that the dominant computer manufacturing company was releasing

a new model with operating characteristics that make it incompatible with Conway's hardware. Because users of automated machine tools want to be able to take advantage of the latest advances in machine tool and computer technology, Conway was forced to adapt its old equipment to the new standards at a high cost. It could not recover this cost, though, by charging higher leasing rates. Thus, profits never reached the levels that had been anticipated. At the same time, Conway had to revamp most of its older computer control programs at considerable cost to run under the new system. The net result was that profits skidded from

$30 million in 2003 to $ 520,000 in 2004, then to a loss of $24 million in 2005.

The sharp earnings decline, coming at a time when computer stocks were also weak, drove the price of the stock down from its 2003 high of $200 to a low of $10 per share. The fall in the price of the stock reduced the value of the stock that the three founders had put up

as collateral for their personal bank loans. When the market value of the securities dropped below the amount of the loans, the bank, acting under a clause in the loan contract, sold the pledged securities on the open market to generate funds to repay the bank loan. This very large sale further depressed the price of Conway's stock, so the proceeds from the stock sale were not sufficient to retire the bank loan. The bank then sued the three founders for the deficit and won a judgment that required the founders to turn their other stocks over to the bank. This additional stock was still not sufficient to pay off the loan in full, so finally the three men declared personal bankruptcy. Thus, in just six years, each of the founders saw his net worth go from $60,000 to $60 million to zero.

The corporation itself was badly damaged by this series of events, but it remained intact. When the three major stockholders lost their shares in the company, the large institutional investors, who now had control of the firm, decided to put in a completely new board of directors and to install Karl Robinson as president and Chief executive officer. The institutions would naturally have preferred to sell their holdings of the stock, but they realized that if they attempted to do so they would further depress the market; they were "locked in".

Robinson was given significant stock options in the company and was told that he was

expected to return the firm's lost luster. At the last annual meeting there had been some

debate among the institutional stockholders concerning the firm's underlying philosophy. The

more aggressive institutions wanted the company to take more chances, while the conservative holders preferred a cautious approach. The issue was never resolved, and Robinson concluded that he could decide the risk posture of the firm for himself.

Robinson was certain that his own position would be on solid ground if he followed a high-risk, high-return policy-and was successful. His stock options under these conditions would be extremely valuable, and his salary would be assured. He also knew that he would be out of a job if he followed such a policy and the company was not successful. On the other hand, he was not altogether sure what his position would be if he followed a conservative policy. The company could survive and earn a modest profit, but he might still end up losing his job.

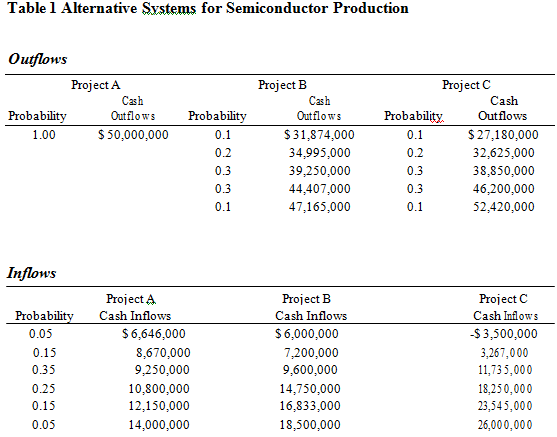

The first major decision Robinson must make involves a manufacturing technology for producing very large scale integrated (VLSI) circuits that form the heart of a new generation of testing equipment that can be used in extremely hot or cold environments. Three alternative processes are available, and some information on these methods is presented in Table 1. With Project A, Monolithic Business Machines, Inc. would provide Conway with all necessary equipment for manufacturing the very large integrated circuits. The initial one-time cost of this equipment would be $50 million. The actual cash inflows from this system would depend partly on sales of the new service and also on the level of mainly variable operating costs incurred by Conway. Project B calls for Conway to build its own production equipment but to license the Monolithic Business Machines process for making the large semiconductor chips. Initial costs with this system are not known with certainty, and it will obligate the firm to cover a substantially higher level of fixed operating costs than would be required for Project A. Project C calls for the immediate implementation, without preliminary testing, of a production process now in the final stages of development

by Conway. This alternative would avoid the expense of license fees, but production costs, quality control standards, and the reliability of the chips produced by the new method are highly uncertain.

Robinson noted that if the worst possible cash inflows resulted from Project C, Conway would be insolvent and would be forced to declare bankruptcy. All of the projects' cash outflows will be incurred in the first year. For lack of better information, he estimates that the actual first-year cash inflow from each project, whatever the flow turns out to be, will continue for the entire ten-year life of each project. Of course, if the large first year loss on Project C is incurred, the company will be bankrupt.

QUESTIONS

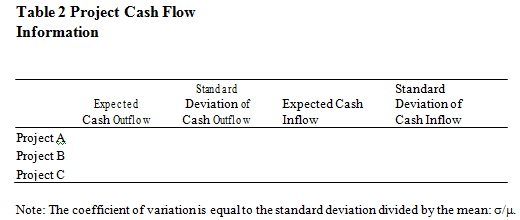

1. Robinson realises how important his first major decision is, not only to Conway but also to his own future. Therefore, he has asked that quantifiable data upon which he will base his final decision be compiled and presented to him. Such data is in the format shown in Table 2. You must complete the blank cells for all three projects. Based on these data, which project appears to be most risky? Least risky?

2. Calculate the internal rate of return on each project, based on expected values of the inflows and outflows.

3. Determine the expected net present value of each project, based on expected values of inflows and outflows. Assume that a 20 percent cost-of-capital is appropriate for Conway.

4. With the cash flow patterns given in the case, could the net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR) result in conflicting rankings?

5. Is it reasonable to use a 20 percent cost-of-capital for each of the projects? What methods of dealing with risk are available to Robinson? Assuming that 20 percent is a reasonable cost-of-capital for an average project in the computer control industry, what are reasonable costs of capital for these projects? Explain your proposed calculations and discuss other required information, if any.

6. Assume that Robinson instructs you to use different risk-adjusted discount rates for each project, and that he suggests that 14 percent is reasonable for Project A, 20 percent for Project B, and 28 percent for Project C. Calculate the risk-adjusted net present values for each project. Do conflicting rankings for the risk-adjusted NPV and IRR occur? If 20 percent is used to evaluate B, what costs-of-capital for A and C would make them appear equally as good as B?

7. Assume that Robinson's job as president of Conway Control & Instrument Corporation is to maximize the value of the firm and thereby maximize the stockholders' wealth. Disregard his personal situation and feelings. Which approach do you think should be taken-an aggressive one or a conservative one? Now consider how Robinson's personal situation might affect his decision; that is, could his personal situation cause him to make a decision that is not in the best interest of the stockholders? Which of the projects should Robinson accept under each assumption?

8. If the returns from Projects A, B, and C had strong negative correlation with the normal expected earnings of most firms in the economy would this affect your estimates of expected NPV? Would you still consider the most risky project you answered in Question 1 to be the riskiest project? How would it affect the overall riskiness of the firm? The overall cost-of-capital?